The rural economies of the Sudano-Sahel are experiencing a dramatic upheaval, and the development and governance of rural rangelands are often a source of tension between pastoral groups and state governments. Many policymakers have viewed pastoralism as incompatible with a modern economy and a practice that should be phased out in favor of other forms of production. This attitude has further pushed pastoral voices to the margins (see Module – Governance and Rule of Law). Critics of pastoralism have cited overgrazing, soil erosion, and desertification as inevitable conclusions of pastoral practices, influenced by the prevailing narrative of the “Tragedy of the Commons.” Though these arguments have been widely challenged by many policymakers and scientists, they continue to inform development policies.

Formalized codes governing land ownership from the colonial-era onward did not recognize customary rights to access pasture or water, as many countries saw the expansion of large-scale agriculture as the key to growth and a settled population as an essential source of tax revenue. Development investments have focused on intensifying food production. This can be seen in the shift from smallholder farms to large private conglomerates, and the development of a market for animal genetic material and feed from foreign markets to increase the size and output of Sahelian cattle.

These changes often appear to benefit investors and economies overseas at the expense of local producers, and have increased competition between pastoralists, local farmers, and private investors for land. Loss of land means loss of subsistence for rural communities, yet such policies are imposed from above without due consideration of their consequences. The assumption is often made that privatization (or, in some cases, conservation and tourism) will generate employment for local pastoralists and farmers, creating a “win-win” for all parties. The results have been mixed.

In much of the rural Sudano-Sahel, pastoralists depend on land and resources that are controlled by the State, even if these lands have historically been governed by customary leaders. Customary rights to land are not legally binding and may be upended by state institutions or companies when land is traded or loaned for private use. Legal reforms to land tenure laws can be one method for replacing zero-sum competition over land between farmers and pastoralists with equitable and easily understood regulatory frameworks. External interveners are frequently involved in providing technical assistance to these reform processes. When done well, interventions can reduce tension over land use by facilitating consultation with local communities, identifying points of conflict between state law and customary practice, and putting pressure on national or state governments to institute reforms that align with accepted principles for governance (see the African Union’s Policy Framework for Pastoralism in Africa or the FAO’s Improving Governance of Pastoral Lands).

In 1993, the Government of Niger instituted a new Rural Code to improve management practices for rural lands and replace an informal system in which land rights were largely controlled by traditional chiefs. The Rural Code was not intended to wholly subvert customary practices; it recognized property rights that were acquired by customary law. This included recognizing that pastoralists have priority access rights to land and water in their home areas (i.e., the territory that they live in for most of the year between migrations). The 2010 Water Code further expanded access rights for pastoralists by making public water access points accessible to all, even pastoralists from other countries. These public water points are supposed to be governed by a Management Committee, though the pastoralists who do not stay close to these water points year-round are often underrepresented in these governing bodies.

Photo: Well in the Dosso district of Niger. Credit: Nasque, CC-BY-SA 4.0

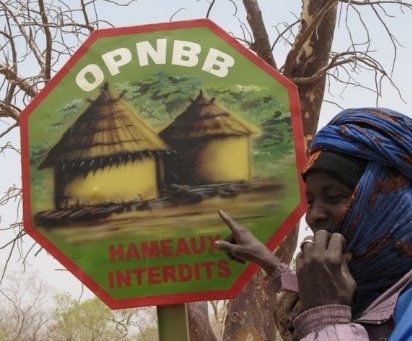

Risks of conflict between pastoralists and local communities need to be considered in long-term local, national, and regional plans for development. The interventions outlined in this Toolkit will have limited impact unless they are reinforced by supportive institutions, funding, and political buy-in. Pastoralists depend on access to common resources, particularly water, during their migrations. Historically, watering and grazing sites are demarcated and maintained per local custom. Yet the traditional practices for negotiating access to public or shared resources have been strained by expanding livestock production, agriculture, and private rangeland development. Improved physical infrastructure – such as markers for migration corridors or grazing reserves, public wells or other water access points, and checkpoints where herders can access veterinary care – can help prevent transhumance from becoming a source of confrontation and conflict.

In 1965, Nigeria’s northern regional government developed the Northern Region Grazing Reserves Law, which created corridors for the passage of migrating livestock and 415 grazing reserves throughout the country. The reserves were envisioned to section off large swathes of land to be exclusively used by herders to graze their livestock. While initially considered a solution to the increasing conflicts between pastoralists and farmers, population growth, urbanization, and migration encroached on these designated areas, reducing herders’ access to and usage of the reserves. Pastoralists were often unable to find sufficient pasture and water within the reserves due to irregular rainfall and little maintenance by state and federal governments. Maintaining their livestock in one place also increased herd vulnerability to disease and banditry, which drove some to move beyond the boundaries of the reserves.

Photo: An aerial view of a Fulani village in the Kachia Grazing Reserve in Nigeria. Credit: Florian Plaucheur/AFP via Getty Images.

In shared landscapes, proactive and participatory management of land and water resources is essential to preventing conflict. Instituting grazing agreements or demarcating transhumance corridors, for example, can help set boundaries between farmland and pastoral land. For these practices to be effective, they need to balance the interests of all stakeholders, including both community leaders and state authorities. Even well-designed management schemes can break down when they are not adhered to or when they disenfranchise one group (as has often happened with pastoralists). External interveners can play a crucial role in promoting participatory management by facilitating consultations with representatives of pastoralist and farming communities or providing technical training to local councils or customary leaders.

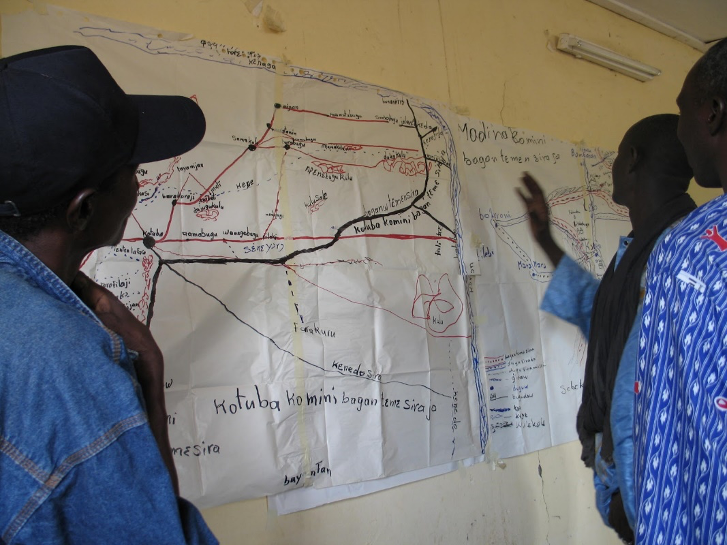

Even though pastoral livestock often migrate along consistent routes, these corridors may lack formal recognition and protection, leaving open the risk for that land to be appropriated for cultivation or other purposes. In North and South Kordofan, Sudan, SOS Sahel engaged leaders of farming and pastoralist communities to conduct a participatory identification and demarcation of these corridors to distinguish them from farmland. Demarcation through community consultation was the first step in a longer effort aimed at social cohesion and collaborative rangeland management. When these corridors threatened to disrupt water access, communities worked to rehabilitate water ponds (haffirs) using sand dams. For long-term maintenance, SOS Sahel supported joint committees charged with the upkeep of these corridors and addressing any related disputes.

Along the Nigeria-Niger border, the Programme d’Appui au Secteur de l’Elevage (PASEL), supported by Veterinaires Sans Frontieres, led a similar effort to secure transhumance corridors. PASEL established a series of Technical Corridors of Passage Committees (CTCP) led by sub-prefecture officials and traditional chiefs. They identified corridors and rest stops in consultation with local farming and pastoralist communities. Once demarcated, the corridors were overseen by monitoring committees composed of village chiefs, farmers and herders. Monitoring committees were tasked to ensure that corridor lanes were respected, and that any related livestock disputes were addressed.

Photo: Local stakeholders discuss a map of transhumance routes in Mali. Credit: Leif Brottem

Mobile pastoralist communities often lack access to basic social services – education, medical care, job training – that are typically provided in urban centers. The lack of access can create a society set apart, limiting opportunities for youth (or others) to pursue other livelihoods or move into new social systems. Targeted mobile service delivery programs, like the use of “field schools,” can connect remote and mobile populations with social services and even socialize good practices for cooperation with sedentary communities. In addition to the delivery of social services, there is also value in expanding access to financial services, which are an essential resource for transforming pastoral livelihoods and lifestyles that are generally inaccessible for nomadic populations.

Lack of access to the education services available in major population centers limits pastoralists’ ability to learn and adopt new techniques to deal with increasing pressures from climate change or changing land tenure systems. This can leave pastoralists vulnerable to environmental shocks, zoonotic (animal-based) diseases, and displacement by commercial development, and leave them with limited economic alternatives outside of illicit activities. Pastoralist field schools – a model originally applied in Kenya but since adopted elsewhere – has been one solution to fill this gap. Pastoralist field schools typically consist of a small group of pastoralists who meet regularly with an experienced facilitator and talk through good practices or innovative solutions to improve their livestock production or adapt to stressors like climate change. Rather than imposing external reforms to pastoral livelihoods, this is meant to be a process of capturing and building upon local knowledge and supporting pastoralists as they adapt to the emerging challenges in their ecosystem.

Field schools can also be used to provide more basic education services – such as literacy programs – to the children who aren’t able to attend fixed schools. The federal government of Nigeria, for example, has formalized these education services through the National Commission of Nomadic Education. Their efforts can range from the setting up temporary huts or structures along nomadic routes to the use of interactive radio instruction to broadcast lessons on numeracy, literacy, and basic life skills to nomadic adults and children as a way to supplement the limited time for in-person instruction.

Photo: Children of pastoralists learn attend school under a tree in Somaliland. Credit: In Pictures Ltd./ Corbis via Getty Images

Development initiatives aimed at helping rural communities and pastoralists modernize their practices will inadvertently alter relationships between pastoralists and other communities sharing the landscape. Traditional assessments are often not suited to account for nomadic populations, as they tend to prioritize the permanent residents of a community who are more visible. Evaluating the socio-political, economic or environmental repercussions of any development effort, no matter its size or scale, is essential to any program design phase. This may require tapping the specialized expertise of anthropologists, political economy experts, or others who understand the nuances of engaging with pastoralist populations.

In 2015, the World Bank launched two major development initiatives focused on support for pastoralism and agro-pastoralism: the Projet Régional d’Appui au Pastoralisme au Sahel (PRAPS) in six Sahelian countries, and the Regional Pastoral Livelihoods Resilience Project (RPLRP) in three East African countries. Both initiatives sought a substantial investment in local infrastructure and resource management practices in contexts where resource access was a flashpoint for conflict between pastoralist and farming communities. Recognizing the need to prevent these investments from triggering further hostilities, the Bank developed a specialized set of tools to train and sensitize implementers on the relationship between conflict and pastoral development. Under the Pastoralism and Stability in the Sahel and Horn of Africa (PASSHA) program, the Bank embedded dedicated conflict experts with the implementing organizations for both PRAPS and RPLRP who could train project staff on how to identify potential risks of conflict and including in the use of a Practical Guide on Conflict Sensitivity and Prevention for Livestock Sector Development Projects in Sub-Saharan Pastoral Areas and a Field Level Project Appraisal Checklist.

Photo: Man with a rifle walks among cattle in Udier, South Sudan. Credit: Simon Maina/AFP via Getty Images