Far from urban centers of decision-making, pastoralists and the rural populations with whom they share the landscape often have little voice in State government. These populations face barriers to participation in public institutions, formulating their concerns in policy-ready language, and ensuring these interests are represented. However, pastoralists seeking to protect their freedoms from central authorities may not see policy measures as a solution, see the government as their ally, or see a lack of civic participation as a problem. Most pastoralists find their interests better served through long-standing peer networks or customary institutions, rather than the centralized governments found in many states of the Sudano-Sahel. Interventions that strengthen state institutions at the local or national level that are known to neglect pastoralist concerns risk inciting further polarization.

The tensions between pastoral communities and central authorities have a long historical legacy, beginning in colonial land management and continuing through post-independence. While land tenure policies and border controls in some states have been revised or superseded by legislation that protects pastoral livelihoods, this legacy of state hostility is not quickly forgotten. These suspicions are confirmed when states impose fees on border crossings, restrict pastoral movements, or privatize public lands. Circumventing state control by avoiding border checkpoints or rejecting cattle licensing systems are common practices. This non-compliance, in turn, feeds stereotypes of pastoralists as criminals.

Increasing the representation of pastoralist communities in state institutions can help assuage these tensions but is not always feasible. Malian pastoralists who migrate into Nigeria are directly affected by Nigerian policies but will not have the same opportunities to affect political decision-making as Nigerian citizens. In many regions, pastoral groups are an extreme demographic minority who face the same obstacles to inclusion as any minority group but compounded by their lifestyle that keeps them distant from political centers.

Yet the problem of exclusion varies between contexts. In some sub-regions, pastoralist ethnic groups comprise large and influential political constituencies that dominate local politics, even if they are a minority at the national level. This is a concern of farming communities in central Mali, for example, who decry that they have been marginalized by pastoralist influence in policy circles. This favoritism is reportedly due to the political elites who own large herds that are serviced by paid pastoralists, a common phenomenon across the Sudano-Sahel.

Operating in remote areas and at the margins of state authority, pastoralists are rarely in a position to advocate effectively or to challenge state policy through official channels. They often lack direct experience with legislative process and familiarity with participatory governance. Supporting the formation of representative bodies to help pastoralists defend their interests is a starting point. Trade associations for pastoralists are present already in most Sudano-Sahelian countries. However, they, and other civil society networks, may lack the technical knowledge to pursue legislative reforms on complex issues such as land tenure or may serve primarily as a platform for traditional leaders rather than representing the diverse voices of all pastoralists in their network.

Across the Sudano-Sahel, trade associations and civil society networks work to bridge the gap between centralized policy decision-making and remote pastoral populations. Founded in Burkina Faso in 1998, Le Réseau de Communication sur le Pastoralisme (RECOPA) is one such network that serves both as a focal point for disseminating information on livestock management to the pastoralist member groups, and to advise local and national institutions on policies impacting pastoralists. In Nigeria, the Forum on Farmer-Herder Relations in Nigeria (FFARN) brings together academics, civil society, and representatives of pastoral and farming associations to share research and pursue joint advocacy. The FFARN has served as a platform for civil society voices to produce locally-led analyses of Nigerian state and federal policies, and to advise policy makers within Nigeria and internationally on the local dynamics of farmer-herder conflict.

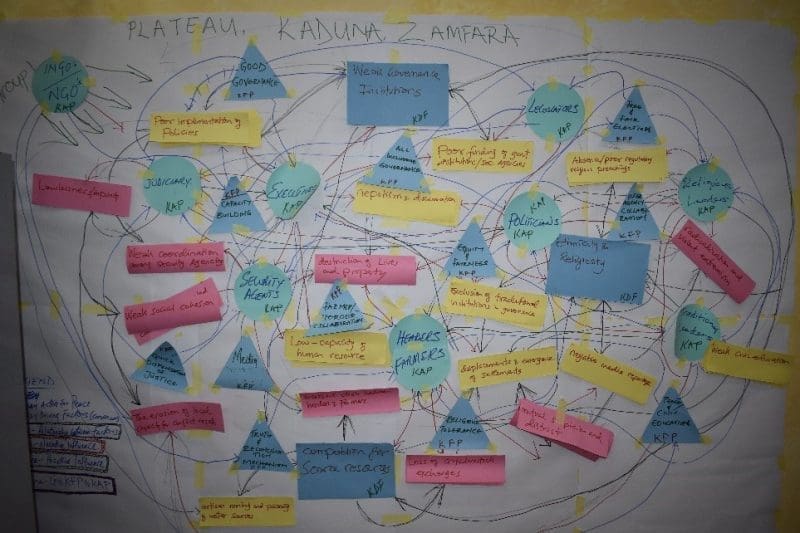

Photo: Members of the Forum on Farmer-Herder Relations in Nigeria meet to discuss advocacy strategies. Credit: Search for Common Ground

Pastoralists, who have limited access to information and low levels of trust in central authorities, are often unfamiliar with the policies that govern their livelihoods. Local customs are generally far more important, as the State has limited capacity to enforce official policies in peripheral territory. However, low levels of familiarity with state policy can leave pastoralists vulnerable to being penalized for violations that they are unaware of, further exacerbating tensions. It also limits pastoralists’ ability to hold duty-bearers accountable for upholding their established rights, such as the right to move livestock freely across borders, which is enshrined in regional agreements like the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Transhumance Protocol. Awareness-raising initiatives tailored to pastoralist populations can help prevent real or perceived abuses by government authorities. Connecting pastoralist communities with mobile paralegal services is one way to bridge this gap.

Pastoralist communities in Kenya, as elsewhere, have depended on the ability of their community to hold land in common so that they can maintain large areas for grazing and mobility. This practice was given legal recognition through the 2016 Community Land Act, which allows groups to register their land as a collective, so that the land cannot be divided and sold off without the consent of the group. This practice has become common and, in some cases, pushes pastoralists to search for new grazing land, creating competition and conflict with neighboring communities. To help communities assert their claims to communal land ownership, organizations like Namati, Samburu Women’s Trust, Indigenous Movement for Peace Advancement and Conflict Transformation, Kenya Land Alliance, and Il’laramatak Community Concerns have trained members of pastoralist communities as paralegals. Pastoralist paralegals in communities like Lengurma and Kuku not only guided their community through the process of registration, they also helped organize demonstrations and advocacy to local officials that helped safeguard their rights and prevent the private sale of land.

Photo: A farmer in Kenya looks over his land to monitor for passing cattle. Credit: Omar Mwandaro.

Along the border between the CAR and Chad, low levels of trust between pastoralists and border agents has undermined effective border management. Pastoralists, concerned that they will be detained or fined for taking their cattle across the border as they have done for years, avoid official checkpoints. Border agents, in turn, are frustrated over their inability to monitor who is coming and going in a region that has been heavily impacted by criminal activity and NSAGs. In an effort to establish a baseline of trust, in 2019 the International Organization for Migration (IOM) developed a guide to help pastoralists understand their legal rights, so they could feel confident that they could move through border checkpoints without being unfairly exploited. The guide has been used as a tool to educate both pastoralist civil society networks and law enforcement officials on the existing frameworks.

Photo: Livestock and pastoralists on the move in Chad. Credit: A. Hissien/I. Bourdjo,

Project Transhumance at Crossroads

While pastoralists and farmers have long maintained customary or informal practices for mediating disputes, these practices are not always appropriate or adequate for providing justice in pastoralism-related conflicts. In South Sudan, for example, some have argued that traditional compensation mechanisms for acts of theft or homicide have broken down as elites have accumulated such large herds that the usual cattle payments no longer have the same impact. Customary justice systems may also be ill-suited to assist traditionally marginalized populations, as is the case for victims of sexual and gender-based violence (see Module 5 – Gender and Women’s Empowerment ). Yet without trusted third parties to address complaints over crop damage, livestock theft, or assault, pastoralists and farmers increasingly seek restitution through violence.

Access to formal justice mechanisms is often limited in the rural and remote areas where pastoralists live and operate. State justice institutions may not be present, their procedures may be unfamiliar, and they may have limited capacity to enforce their decisions. Where the State does exercise control, pastoralism-related crimes may be referred to a wide range of authorities (security forces, municipal government, customary courts) that don’t work in concert and don’t follow the same procedures. In the short term, external interventions can help address these gaps through mobile courts or programs to build consensus among the various local authorities.

Decentralization has been a public sector reform strategy employed by some Sudano-Sahelian states to increase autonomy for local communities who have been frustrated by years of systematic exclusion from political authority. Devolving administrative authority over natural resources from federal to local government ideally creates more accountability to local interests. Vesting control over migration corridors or grazing reserves to local village councils, though, does not automatically result in more inclusive governance of these resources. Interventions that support decentralization should be designed to help reconcile competing rules and customs in resource governance and set into motion participatory governance practices that are accessible to mobile populations.

Mali’s long history of centralized government from the colonial era forward was reversed in 1992 with a new constitution announcing major administrative reforms that decentralized oversight and management of public services, including lands. The aim was to accelerate the pace of rural development by granting sub-national authorities greater autonomy over local resources, infrastructure, jobs and growth, all while strengthening national unity. While promising greater local control over budget, planning, policy and service delivery, the move from theory to practice took years of parliamentary deliberation to draft, approve and transfer legal responsibilities to newly created local communes. These reforms, however, largely failed to accommodate customary laws regarding land ownership and access, resulting in competition between proponents of state rule and traditional authority.

Photo: Pastoralists watch over their herds in Mali. Credit: Leif Brottem